Inside the pages of the old school atlas, the small boy holds the pencil, angling it as he edges around Australia’s shores. My father’s hand has been here, tracing the coast, the grey lead pencil pushed down hard into the paper.

My father’s atlas appeared in the family house pack-up after he died and somehow made it home with me. ‘Could I take it? Just to look at,’ I had asked my mum. I held it tight to get it home. Few of the family records had ever left my parents’ house, and this felt like contraband. Along with the atlas, I took some of dad’s tracing paper; a lined grid book; and a ledger notepad, pages torn out and numbers gone. Things which speak to me of finding a way.

For some time I did not dare to open the atlas. His name alone, scrawled across the torn brown paper cover, was enough to suggest what I might find in its pages. A sort of journey. A charting of a life. A discovery. Now I’m tracing back, beyond my time, to see the boy of ten, a 3-D image arising from a 2-D format, the way a globe grapples with the flatness of a page.

The Atlas cover is a rich blue, and is published by J G Bartholomew. ‘The Complete Atlas, 64 Plates and Index.’ Its spine is broken, revealing staples in the crease of the inside cover. Innards held together. Each of the four heavy duty staples has a clutch of paper in its grip, where something has gone missing. The staples bite like braces in a mouth stuffed with cardboard. What can this atlas tell me?

My father knew that he was born into a world where he had the possibility of travel. His parents had met in London, both travelling on scholarships. He too would win a scholarship when he grew up, taking him to Egypt, and Europe and ‘where else, dad?’ I long to ask.

I have a collection of old atlases, coloured pages filled with pictures of workers, illustrations of commerce, manufacturing, ships and shipping channels; pale pinks and blues, dreamy greens of the seas and lands, Europe changed and redrawn, disputed territories claimed and erased; and here in Australia, the so-called ‘terra nullius’, lines drawn by our colonial markers. The history of the world as they knew it, printed over and bound in textbooks for school children.

But this old school atlas that belonged to my father moves me in a weird, intergenerational, multidimensional, multi-layered way. It’s as if we were walking, side by side. Or sitting at one of those double-seated school desks, mapping out our futures, him daydreaming about Swiss vineyards, me reaching for Irish fields. Both agreeing to meet, somewhere. Both with ink stains on our hands and our own pencilled pathways.

Maps have many purposes. To demarcate, claim dominion, project power. They are used for propaganda, for corralling people, for safe navigation. They chart the subsea undulations. They take us to the tops of mountains, and they speak of dreams. They tell stories. At Cornell University, a collection of maps explores ‘persuasive cartography’. “Viewed as a whole, the Cornell collection is a reminder that although there is beauty in truth, an artfully spun point of view can be quite seductive as well. And no maps—even the most scrupulously researched—are completely free of editorial decisions or points of view.”

On one page, Dad has signed his name across the ‘comparative height of principle mountains.’ His signature starts above the mountains of America and then skims the tip of Mt Blanc, finishing up at the Carpathians and the Urals. I’m standing on a peak with him, looking towards Africa and Australasia.

|

| Comparative Height of Principal Mountains. |

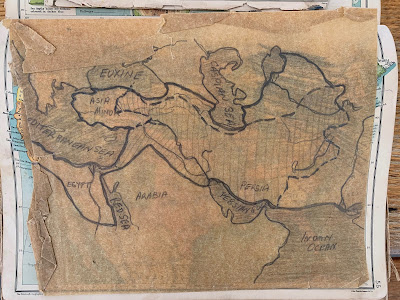

On other pages, it looks like he was mapping the oceans, lines drawn around the Caspian Sea, Mediterranean Sea, Persian Gulf, Indian Ocean, the Red Sea. He plots the course of his forebear, a greylead line pushed into the page, tracking the ship from Liverpool to Barwon Heads. These summer days, I can see that same headland now, over the waves and the saltspray.

There is tracing paper too, the layer we hold over the place below; the way to see through while charting our course. Guided somehow by those who went before, the clear-seeing cartographers and the generations before us. The brown paper tracing paper, which is faded and cracked, has the hand of my father’s sketching on it. Its crinkle is a wrinkle in time.

|

| Tracing the lands, the oceans and seas. |

Across England my father has written: ‘slate, herrings, cod, rocks, fish, coal’. In Connemare Ireland, where I went and saw the marble, he has written: ‘marble’.

On the back page, there is a tiny rip through the paper cover–once again Dad has signed his name, this time in red crayon. I scan the index at the back to see if there are any towns that dad has left a mark next to–keen to find an anchor point for his, and my, journeys–but there are none. It leaves the index open to all possibilities.

Who are we, as we head out into the world? What does the child’s address and signature hold? Crayons on a page, torn tracing paper, a grey lead pencil lightly scaling mountains, hugging the shore; the feathers of undersea currents brushing our hands as we flow with the passage of our lives. For me, dad’s atlas speaks of home: the seeking of it, the leaving of it, the making sense of one’s place within the world. I’ll never know the full story.

First published in The Guardian, 10 January, 2021

|

| '2,200000 acres' |

Comments

Post a Comment